Tasting Mezcal in Matatlán

Santiago Matatlán, a town in the southwestern Mexican state of Oaxaca, was the place that transformed me from a casual mezcal drinker to an outspoken mezcal enthusiast—which is fitting, as it’s considered the “World Capital of Mezcal.” After I landed in the relatively tiny town of about 10,000 people, the first palenque (mezcal distillery) that I visited was Mezcal Desde la Eternidad, a family-owned, mother-daughter-run artisanal mezcal superstore located on the town’s main road, Carretera Internacional.

Okay, so it wasn’t technically a superstore, but this palenque had more varieties of artisanal mezcal in one spot than I’d ever seen. The back wall was lined with more than 30 varieties that the team had produced by hand, from popular Espadins to one-of-a-kind blends like their Ensamble (made from two wild agaves called Jabali and Tepeztate) and their generations-old medicinal mezcals infused with local herbs known to help with ailments like indigestion.

The front of their palenque was a museum of mezcal on its own. A quick walk around the corner, I saw a massive hand-painted mural of a man surrounded by maguey (agave plants). In talking to half-owner Hortensia Hernández Martínez, I learned that the man in the mural was her husband, Juan Hernández Méndez, who had passed away a few years prior. He had been the maestro mezcalero—master mezcal maker—who’d run this family’s palenque. After Juan passed away, Hortensia and her daughter, Lidia, decided to keep the family business alive and continue producing mezcal. With so few Indigenous women producing mezcal to begin with, meeting a mother-daughter team felt rare and unforgettable.

The vast majority of residents in Matatlán—as it’s informally known—are Zapotec, an autonomous Indigenous group native to this region of Mexico. Today, you’ll find Indigenous mezcal producers who come from long lines of producers that predate the Spanish colonization of Mexico in 1521. Traditionally, many producers built (and still build) their palenques off of their homes, and pre-colonization, they were not required to register them as businesses with the government.

After colonization, however, registering a mezcal business became expensive, and many natives couldn’t afford it. Some producers whose families have been making mezcal for generations say they are second-, third-, or fourth-generation producers, indicating how long the business has been registered, not necessarily how long they’ve been making mezcal.

While Matatlán houses a number of internationally recognized mezcal companies, there are countless Indigenous-owned mezcal brands operating out of palenques all over town. It’s difficult to say just how many people are involved in Matatlán’s mezcal industry, but it’s estimated that the state of Oaxaca creates over 90% of all mezcal globally, and Matatlán produces much of that total.

Mezcal, like tequila, is a high-proof, clear liquor made from agave plants. But, that’s where the similarities end. Tequila is made using a more industrialized process, whereas mezcal is produced through an artisanal process that dates back to pre-Hispanic Mexico. Mezcal also tends to have a higher alcohol content, a wider breadth of flavors characterized by their smokiness, and can be made from any agave plant, whereas tequila can only be made from Blue Weber Agave.

The process of making mezcal takes a lot of strength, as some agaves weigh well over 500 pounds. It involves cultivating the agaves (which take anywhere from 8 to 35 years to mature), harvesting them, transporting them from the field to the palenque (which can be miles away), roasting them in a massive outdoor oven, taking the roasted pieces and separating the juices from the fibers (traditionally by using a horse-drawn mill), gathering the juice to ferment, and only then beginning the distillation process. The vast majority of this is done by hand, particularly within smaller, native-owned businesses.

This part of Oaxaca, tucked between some of the state’s most legendary mountain ranges, is vastly different from Oaxaca City, which sits only an hour away. The climate is much drier than the lush, coastal parts of the state, which is ideal for healthy maguey (and makes moisturizer a must). The land is rich with about 30 varieties of agaves, the most popular of which is Espadin, used to make 80–90% of all mezcals. The truly unique mezcals, though, are made from wild agaves, such as Cuishe and Tepeztate, which are found in the bordering mountains. Finding them can take days or weeks, which makes trying them as a beverage journalist all the more inviting.

In Matatlán, a mezcal tasting can be very difficult without a guide, especially if you plan to visit Indigenous-owned palenques where the owners largely speak Zapotec. This is why I opted to take a tour with Liliana "Lily" Palma Santos, a Zapotec woman who runs a travel company dedicated to sharing her culture with travelers. She and her team are all locals who speak English, Spanish, and Zapotec, and have been building a community of native mezcal producers since 2021.

Lily pointed out that when a palenque is attached to a home, it’s a good sign that you’ve found a native producer. But, just because a palenque is attached to someone’s home doesn’t mean that it’s small. Liberemos el Alma, for instance, was a smaller operation, while Lopez Real is particularly large and produces mezcal that’s distributed throughout the US and Japan. Some palenques have small agave fields onsite, while their larger fields are found outside of town in the vast open plains between the town and the mountains. (If possible, I encourage visitors to take a tour of the agave fields—just remember to wear shoes that you don’t mind getting dirty.)

Over the course of my 10-day trip, I visited seven Indigenous-owned palenques, all run by women. Some were established in the local community, like Mezcal Desde la Eternidad, which had the widest variety of mezcal of the producers I visited, including several medicinal varieties. Some of their mezcals, like the 14 Hierbas medicinal mezcal, were on the sweeter side with some herbal notes; it tasted more like a very-spiked tea than the common smoky mezcal. I even bought a bottle of their Ensamble, which has a subtle smoke and a lingering earthiness that I’ve grown to crave.

Liberemos de Alma produced a “Dia de los Muertos” mezcal that was distilled with the fruit blend that the producer’s family usually puts on their altars for the Day of the Dead. This mezcal had the lingering taste of tropical fruit punch, minus the cloying sweetness, because of all the fruits added during the distillation process. The specific fruit medley was a family secret, though I detected some red berries in the mix.

Each palenque is run by a different family, which means that, if you are open to listening, they are open to sharing their stories. Sustainability, Indigenous rights and autonomy, gender politics, and many more factors come into play in the producers’ day-to-day lives. While I enjoyed drinking the mezcal and eating Indigenous cuisine each day, the value of hearing Indigenous history was incalculable. For example, Lidia from Mezcal Desde la Eternidad showed me the last row of agaves that her father planted before he died, each agave a form of living history. And Isabel Santiago Hernández, the founder of Liberemos el Alma, shared her excitement about being the first woman in her family line to head a mezcal company.

As someone of African and Taino ancestry—one of the native groups that once flourished across the Caribbean Islands—I accept that I will never fully know much of my history. Between the transatlantic slave trade and the widespread genocide of Indigenous people throughout the Americas and Caribbean, my Afro-Indigenous history is full of unanswerable questions. The fact that Indigenous people and history still have strongholds around the world is a testament to the strength, endurance, and persistence of native peoples.

Zapotec heritage is alive and well among the palenques of Matatlán, and you can feel the celebration of that history in every glass of mezcal. While the mezcal alone is worth the trip, the stories you're bound to hear make it all the more worth it.

Getting there

- Matatlán is located near the center of Oaxaca, Mexico, with the only nearby international airport being Oaxaca International Airport (OAX). There’s no public transportation to go to or from the airport, so you’ll either need to rent a car or schedule a taxi to get to your destination. If you plan your visit through Zapotec Travel, Lily will organize transportation for you. Have cash on hand in the form of Mexican pesos for payment.

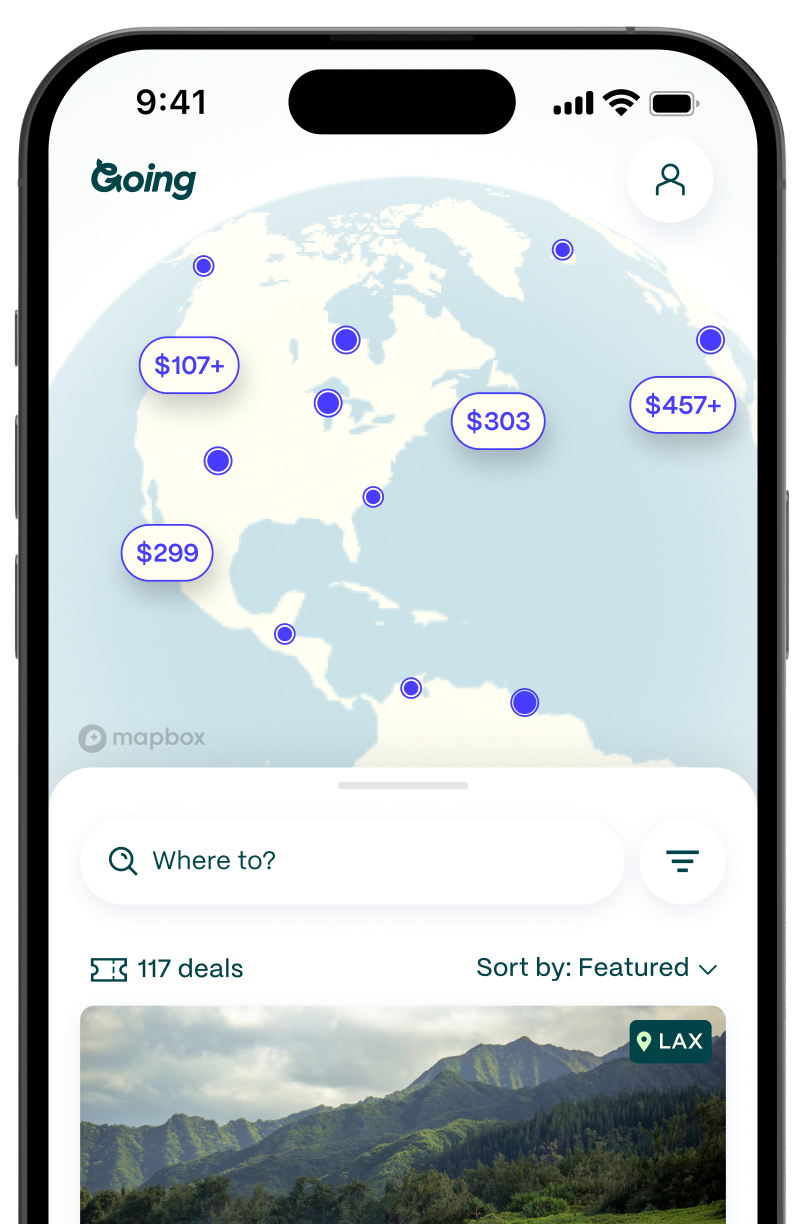

- Average Going deal for cheap flights to Oaxaca: $276 roundtrip

How to do it

- Best time to go: August–March are the best months to visit. April and May are the hottest months (in terms of heat, not necessarily popularity), and June and July are the rainy season.

- Cost: Group agave tours through Zapotec Travel start at 2,530 pesos (about $150 USD) per person for an 8–10 hour tour (min 5 people). Private tours start at 3,800 pesos (about $222) per person. Most mezcal tours in Matatlán start around 1,600 pesos (about $94) per person for a 4-hour tour, though you can find tours of varying lengths and costs.

- Tips and considerations: Leave space in your bags when packing for this trip. All of the palenques have bottles of mezcal that you can purchase at an affordable price ($20–$40 USD). If you’re flying into the US, the TSA website says you can only bring 5 liters of liquor into the country, so choose your bottles wisely. Also, bring solid walking shoes, as the agave fields are no place for heels or white shoes.

Other Mexico guides

Published April 9, 2024

Last updated April 9, 2024